A boy and a girl played on the rug in the sitting room. There was no need for a fire. Outside the city calmed as the lights went out. The mother of the two well dressed handsome children tapped her finger on the tabletop. The household staff sat by quietly while dinner grew cold on the plates.

“Another maté, sir?”

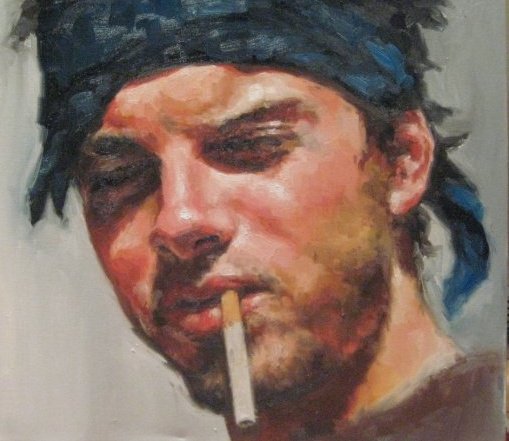

Marcos didn’t want another maté nor another café. The aftertaste in his mouth made vomit seem likely. The streetcorner moved crowded with carts and horses and pedestrians moving by on a million errands, all going somewhere in particular. The coins on the edge of the table confused him. Marcos got up and walked West. The sun is unknowingly merciless; sweat filled the creases in his shirt. He took his sport coat off still walking.

Late afternoon Marcos was at the outer edge of Montevideo.

Some time in the morning Marcos woke on the outskirts of the village Fray Bentos a few less coins in his pocket. The Uruguay river moved near him, strong and beautiful. He felt strong and beautiful, and damp. The dew had wetted his clothing and hair. He waded in. He began to swim. He had not swam against a current like this since boyhood. He remembered the fear in him so small against the water. He did not fear now.

The gaucho called him ‘Montevideo’ again. Marcos spat on the floor. He looked at the spit, bubbly little puddle on the wood. Why had he spit? He brought his eyes back to the dirty man at the table. The man was standing, head toward him, arms back, with a horrid face.

“I like your pretty clothes, Montevideo.” Marcos did not respond. The bartender, fat where he should be thin and thin where should be fat placed a knife down next to Marcos’ glass.

“Outside,” quietly from the bartender.

“Come now, Montevideo. My horse can wear your pretty clothes when you’re dead.” The man’s friends laughed and slapped the table again and again. Marcos did not hesitate. He took the knife and drained the glass. The man with the horrible face, scarred and ugly, unsheathed and raised his knife.

“OUTSIDE,” shouted from the bartender. Marcos showed the door with his knife hand. The man moved facing Marcos, wrapping his poncho on his arm as he did. He went into the dark. Marcos walked toward the door. The bartender stopped him with his fat hand. He took Marcos’ sport coat and wrapped it for him, like the gaucho did. Marcos drunk(?) walked out into the dark to fight in the corona of a lantern. The bartender stood at the door with the kitchen’s cleaver. The ugly guacho’s two friends remained at the table. They heard a shout, a laugh, and feet shuffling dirt.

Marcos entered. The two men sat down and finished their wine. Marcos’ bled to the tips of his fingers, no farther. He sat down. The bartender poured him a wine.

The man from Montevideo scratched his beard. Atop a horse you can see everything, more than from a tall building. You look all around you. The men below you are just that, below you. From the Uruguay river he’d walked and swam to the first man he killed. He took the man’s horse and poncho. He let out toward Cordoba.

Six months led him not to the life of a gaucho. Childhood gaucho stories were not this. He was a thief, a robber, a murderer. All day he was satisfied, fantastic when drunk, miserably so with women.

Six men rode behind him. They shared the fire, not much else. Each man gave part of what he took, which the man from Montevideo usually left where it lay. The men picked the things back up for themselves. He took women and wine always, not much more than that. Tonight he took little of the roast goat and drank most of the wine. Always taciturn until the wine struck him, then he told jokes and talked of fortunes.

A year put twenty men behind him, his reputation numbered them fifty. Bandits. He’d raped across most of Argentina, murdered and burned and stolen more than an invading army. He’d killed twenty men wearing national colors, five of his men looking for glory in fair combat. The men talked of more women and more food and more coin and paper in their pockets. The men had desires; the man from Montevideo quietly provided.

Macedonio was the man close to the throne on the horse. Large, cordial, and ruthless. The man from Montevideo now told his jokes only to him.

The last night, Macedonio, glowing with wine and excitement asked cordially and quietly the man from Montevideo’s name. The man from Montevideo paled.

“I am Marcos Garcia. It has become dark and I have drank of too much wine. My wife and children sit by the table while my dinner grows cold. I have not seen them in a year. Macedonio,” he laughed a little at this point, “I had forgotten it all. One Maté at lunch and I forgot everything.” The man from Montevideo laughed again, and then quieted. “Macedonio, I am leaving. Thank you for being a friend to me. Those outside will listen to you now as you have listened to me. I have remembered myself. I am not this man you have followed. You are not the man who has followed. I will be leaving now.”

Macedonio sat stunned with his cup in hand. Never had the man from Montevideo spoken this much at once. Never had he said anything like this. He couldn’t rise as the man now known as Marcos Garcia exited the tent. Macedonio did not follow until the sound of the horse was gone. The camp was silent, waiting. He slowly left the tent.

“Go back to your homes. We had all forgotten.” The men sat dumbfounded. Macedonio mounted his horse and rode south to Buenos Aires. Slowly, one after another the men mounted horses and left in all directions, speaking to themselves in exasperation and relief and fear.

Marcos came to the Uruguay river. He patted his horse on the neck, then hard on the flanks. He was alone. It was morning again. The river moved the same as the year before. But he was afraid now. The water was cold. His feet never felt the other bank.

The staff cleared away his plate..